Peak Pobeda (official name in Kyrgyz - Жеңиш чокусу / Jengish Chokusu) is a 7,439 m mountain, the highest point of the Tien Shan range and the highest summit in Kyrgyzstan. Bordering China, the mountain is located in the eastern part of the Kakshaal-Too Range (Ak-Suu District, Issyk-Kul Region) right on the border with the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of the PRC. Peak Pobeda is the planet’s northernmost seven-thousander, whose climate is extraordinarily harsh due to its latitude. Along with Lenin Peak, Communism Peak (now Ismoil Somoni Peak), Korzhenevskaya Peak, and Khan Tengri, this summit is part of the “Snow Leopard” program - an honorary title awarded for climbing all the highest mountains of the former USSR.

History of discovery and naming

Back in 1931, Soviet mountaineer Mikhail Pogrebetsky, standing on the summit of Khan Tengri (6,995 m), noticed a gigantic unknown mountain to the south that struck him with its scale. In 1938, an expedition led by Avgust Letavet set off for this summit and, after 11 days of climbing, successfully reached a new height. The climbers named it the “20th Anniversary of Komsomol Peak,” as the expedition took place during the 20th anniversary of the VLKSM (Komsomol). However, due to dense cloud cover, the team could not determine the exact elevation and measured only 6,930 m using an aneroid barometer.

Only in 1943 did military topographers from an expedition led by Pavel Rapasov conduct a detailed survey of the area - it turned out the unknown mountain was almost half a kilometer higher than Khan Tengri. The measured height of 7,439 m made this summit the highest in the Tien Shan. Initially, the topographers named it “Military Topographers’ Peak,” but in 1946, in honor of victory in World War II, it was renamed and received its current name, “Peak Pobeda” (“Victory Peak”). In the same year, the summit was firmly established as the second highest in the USSR, surpassed only by Communism Peak (7,495 m).

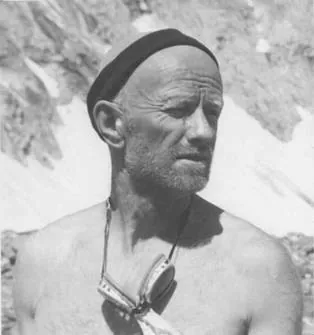

The first officially recognized ascent of Peak Pobeda took place on 30 August 1956: a joint team of Soviet climbers led by the legendary Vitaliy Abalakov reached the summit. (The previously considered successful 1938 attempt was later questioned due to an error in altitude determination.) Since then, Peak Pobeda has attracted the most experienced alpinists, yet up until the 1980s it remained a very rare objective due to its reputation and difficulty.

Harsh climate and climbing difficulty

Peak Pobeda is considered one of the most inaccessible and dangerous mountain summits in the world. Its extremely northern location for such an altitude creates a climate comparable to Himalayan eight-thousanders. Even in summer, at elevations above 7,000 meters, temperatures can drop to -40°C, and winds can reach hurricane-force 50 m/s. Weather windows are extremely short - usually just 2-3 weeks in August when summit attempts are possible. The slightest change in weather - a sudden blizzard, sharp cold snap, or fog - turns the climb into a deadly ordeal. Due to the terrain, gigantic cornices form along the ridges; their collapse or avalanches threaten everyone on the route. Unpredictable weather and a short season force climbers to “catch” weather windows for a summit push. Breaking unwritten safety rules (for example, continuing the ascent in winds over 30 km/h or right after snowfall) on Peak Pobeda almost certainly leads to tragedy.

Before a summit bid, climbers usually carry out prolonged acclimatization: experience shows the need for at least two nights above 6,400 m (ideally around 7,000 m) before attempting Pobeda. Often, a preparatory climb is made on a more “approachable” seven-thousander - Lenin Peak (7,134 m), where one can relatively easily reach camps at 6,400-7,000 m and adapt to the altitude. Only after proper acclimatization do expeditions move to the base camp under Pobeda.

Routes, base camps, and technical details

The main base camp for climbing Peak Pobeda is on South Inylchek (the South Inylchek Glacier) at about 4,000 m. Mountaineers usually get there either by a multi-day trek or by helicopter drop from Karakol. From base camp, you get a panorama of two of the Tien Shan’s greatest summits - Peak Pobeda itself and neighboring Khan Tengri (6,995 m).

From base camp, the ascent route runs along the Zvezdochka Glacier to the foot of the peak. The classic route on Pobeda goes via the western summit of the massif - the so-called West Pobeda, also known as Chapaev Peak - and then follows the seemingly endless eastern ridge to the main summit. This route is rated 5B (the highest category of difficulty in the Soviet classification for high-altitude climbs) and is within reach only for climbers of Master of Sport caliber. The distance from the assault camp to the summit is over 10 km along a very high alpine ridge. The ascent is extremely exhausting: after ~7,000 m the path follows a narrow snow cornice where, at the limit of one’s abilities, you must balance, stepping with feet on either side of a knife-edge ridge. Every step at that altitude is a huge effort due to hypoxia, and any misstep can lead to a fall. Overnighting on the ridge is exceedingly difficult - tent platforms are limited, there are cliffs all around, and in bad weather the group is completely exposed. The descent along the same long ridge often turns into a fight for survival, especially if someone in the team is injured - this was starkly confirmed by the recent case of Natalia Nagovitsyna in 2025.

An alternative to the classic line is the Abalakov Route, laid from the north directly to the summit. This path is shorter and more logical: for a well-prepared team it allows an ascent in roughly 3-4 days, avoiding the long traverse of the western ridge. However, the Abalakov Route has a significant drawback - it crosses vast snow plateaus and steep slopes that are extremely avalanche-prone in unfavorable conditions. Instructor and Snow Leopard awardee Ruslan Kolunin noted that he considers the Abalakov Route optimal for a well-prepared group on Pobeda, but warned of the high avalanche risk: “In adverse snow conditions, the large snowfields on the Abalakov Route are very avalanche-prone.” Overall, all lines to the summit demand maximum technical and physical readiness, proficiency in rope-team travel on glaciers and steep slopes, and survival skills for autonomous existence above 7,000 meters.

Danger and statistics: “the mountain that takes lives”

Virtually every ascent of Peak Pobeda carries a life-threatening risk, and tragedies occur here with alarming regularity. By various estimates, the total number of deaths on Pobeda’s slopes exceeds 100 people. Unofficial statistics suggest that almost every third climber ends up remaining on this mountain forever. The likely real mortality rate is about 8% of total summit attempts - one of the highest in world mountaineering for peaks of this class. Moreover, the victims have by no means been only novices or poorly prepared parties - on the contrary, some of the best and most experienced alpinists have perished here. The mountain is justly called unpredictable and untamable - it does not forgive mistakes and imposes its rules even on Masters of Sport.

Since mass ascents began in the 1950s, the sorrowful chronicle of deaths on Peak Pobeda has grown quickly. As early as 1955, the first major tragedy occurred: two Soviet expeditions (from Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan) went for the summit, and 12 climbers from the Almaty team were trapped by a blizzard at around 6,900 m. After several days waiting in a snow cave, their strength ran out - a chaotic descent began, during which 11 people died one after another, and only Ural Usenov miraculously survived and made it down alive. Rescue operations the following year turned into yet another catastrophe: in 1960 a group of ten rescuers fell into an abyss while attempting to lower bodies from the upper camps. Since then, not a decade has gone by without serious incidents on this mountain.

In 2012, tragedy befell one of Russia’s strongest female alpinists - Darya Yashina. Darya and her partner (they were engaged) planned to climb Pobeda in August 2012. During the final summit push, trying to beat an approaching storm, Yashina fell together with a huge snow cornice near the summit and plunged into a two-kilometer void. Her body was never found, even after thorough searches with optics and a helicopter - the storm hindered rescuers, and on 13 August 2012 the operation was officially terminated. Her fiancé Alexander descended alive, but the tragedy shocked the climbing community.

In 2015, renowned Soviet and Russian mountaineer and Snow Leopard awardee Mikhail Ishutin died on the mountain. At 58, Ishutin had successfully climbed Pobeda for the third time as part of a group raising a flag for the 70th anniversary of Victory in WWII. However, during descent his heart stopped - likely due to extreme high-altitude stress. His body was left on the ridge, covered with snow, but could not be brought down because a hurricane broke out. Sadly, Ishutin’s remains lie just a few meters from where, ten years later, Natalia Nagovitsyna became stranded.

Quite recently, in July 2023, four climbers went missing during descent from Peak Pobeda. Experienced guide Dmitry Pavlenko, together with his wife and two clients, summited via the Abalakov Route, but the team lost contact during the descent. GPS tracker data showed that around midnight the team was at ~7,300 m, then within minutes they dropped to ~6,580 m - most likely a fall or night avalanche on 20 July 2023. Debris and traces of the fall were searched for by helicopter, but to no avail - all four are listed as missing.

In the summer of 2025 the mountain claimed the lives of several outstanding alpinists. On 10 August 2025, after summiting, Nikolai Totmyanin - “Uncle Kolya,” a 67-year-old legendary conqueror of the most difficult routes, Piolet d’Or laureate and a six-time Snow Leopard awardee - passed away. Descending from Pobeda, Totmyanin felt unwell (presumably cardiac arrest at altitude); he was evacuated to Bishkek, but the next day his heart failed. In life, Nikolai Anatolyevich particularly emphasized the treacherous nature of this summit. After one successful Pobeda climb he formulated a grim pattern: “...the price for reaching Pobeda’s summit is the life of one or more climbers. If in some year no one dies on Pobeda, that means no one summited” - exceptions, when everyone summits and all survive, he said, are extremely rare.

The tragedy of Natalia Nagovitsyna (August 2025)

The most recent tragic chapter in the history of Peak Pobeda was the August 2025 drama that drew wide public attention. Russian alpinist Natalia Nagovitsyna (47) broke her leg during descent and was left entirely alone at about 7,200 m, unable to continue moving. The incident occurred on 12 August on a ridge section near the rocky outcrop “The Obelisk” (roughly 7,100-7,200 m). Nagovitsyna’s partner - guide Roman Mokrinsky - tried to provide first aid, then, after radioing base camp, was forced to descend alone for help.

A large-scale rescue operation began, followed for two tense weeks by the entire climbing community, hoping for a miracle. By the evening of 13 August, two climbers from Natalia’s group - German mountaineer Günther Siegmund and Italian Luca Sinigaglia - managed to climb back up and reach the victim. They set up a tent for her, left a sleeping bag, food, gas for the stove, and immobilized the broken leg. According to Günther, at that moment Natalia’s condition was “more or less normal” - she had pain relief and shelter from the wind. However, conditions rapidly deteriorated, and contact with her was soon lost. On 14-15 August, Luca and Günther, exhausted by the altitude, began descending themselves - the Italian suffered severe frostbite and soon died on the slope from cerebral edema, never making it to camp.

All resources were thrown into the effort to save Nagovitsyna. On 16 August a Kyrgyz military Mi-8 helicopter with a rescue team attempted to reach the site, but due to a storm made a hard landing on a glacier short of the goal; several rescuers were injured. For several days, volunteers and professional climbers made unsuccessful attempts to climb to Natalia’s location - but high-mountain storms raged, literally pushing people back. By 19 August, a week after the injury, a reconnaissance drone was finally flown to her tent. The footage gave rescuers and loved ones some hope: the video showed a motionless figure in a sleeping bag inside the tent - likely indicating Natalia was still alive. This ray of hope inspired organizers to prepare for another evacuation attempt.

Unfortunately, weather once again ruined the plans. A ground rescue team, assembled from top Kyrgyz, Russian, and Kazakh climbers, was able to reach only the height of Camp 1, after which on 22 August they were forced to retreat due to unbearable conditions and illness of the rescue leader. In parallel, an unprecedented aerial evacuation option was considered - by an Airbus H145 high-altitude helicopter engaged by Kyrgyzstan’s Emergency Ministry. This modern helicopter had previously landed on Aconcagua (6,962 m in the Andes), and Italian pilots were ready to risk flying to 7,200 m. However, on 25 August the weather gave no chance again - the helicopter could not take off from base camp. By 26-27 August it became clear that time had run out: the altitude, cold, and lack of food left no chance of survival after so many days. An official representative of Kyrgyzstan’s EMERCOM stated that, in the experts’ opinion, Natalia Nagovitsyna had most likely died. On 27 August the Kyrgyz authorities declared her missing (formally, she cannot be recognized as deceased without recovery of the body). The heavy news shocked everyone following the drama: despite incredible efforts by rescuers, the impossible could not be achieved - Pobeda once again did not let a person go.

It was a particular sorrow for Natalia that four years earlier her husband had died in the Tien Shan. In 2021, Sergey Nagovitsyn passed away from a stroke at 6,900 m during their joint ascent of Khan Tengri. Natalia stayed with her husband to the end and later placed a memorial plaque on that summit. The decision to return to the mountains and attempt Pobeda in 2025 proved fatal. Experienced guides tried to dissuade her from this risky step due to the group’s insufficient level of preparation, but Nagovitsyna went for the summit push nonetheless... Sadly, the summit was unforgiving. Two weeks of hope ended in tragedy, once again showing how merciless this mountain can be even to the strongest in body and spirit.

Why is rescue on Peak Pobeda almost impossible?

The situation with Natalia Nagovitsyna made many ask: why is it so difficult to rescue people on Peak Pobeda? The fact is that at extreme altitudes (7,000 m and above) rescue operations have never yet succeeded. If a climber cannot descend under their own power, the chances of evacuation approach zero - the effects of terrain, weather, and altitude are too great. As noted by FAR (Russian Mountaineering Federation) senior search-and-rescue coordinator Aleksey Ovchinnikov, in technical difficulty the routes on Peak Pobeda exceed some eight-thousanders. The path to a victim often runs through the same hazards as a normal ascent: avalanche-prone slopes, glacier crevasses, and sections with thin air where rescuers themselves quickly lose strength. Any mistake can add to the casualty count. In addition, at such heights it is extremely difficult to use aircraft - helicopters barely hold in the thin air and are at the mercy of weather whims. Peak Pobeda dictates its own terms, and even modern technologies are sometimes powerless before its character. It is no coincidence that climbers say: “If the mountain allows - you will summit; if it doesn’t - no skill will help.”

Despite everything, every year there are daredevils who test themselves on Pobeda’s slopes. This summit beckons experienced athletes as the last and hardest milestone on the way to the Snow Leopard, testing the limits of their professional skills and strength of spirit. Peak Pobeda remains a greatest challenge - and the tragic stories it keeps serve as a stark reminder of the high price humanity sometimes pays to conquer mountain summits.

Related news