Forgotten Rivers and Mountain Peaks: A Journey Along the Southern Shore of Issyk-Kul is a three-day tour that immerses you in the unique natural beauty of Kyrgyzstan.

- Duration: 3 days.

- Price: from 1300$ 1000$ for group

- Group size: Small group tour

Bishkek is the capital and largest city of Kyrgyzstan, located in the Chuy Valley at the foot of the Kyrgyz Ala-Too Range (northern Tien Shan). The city lies at an altitude of about 700–800 m above sea level and has over 1.3 million inhabitants (2025). Bishkek is the main political, economic, and cultural center of the country. It is known for its straight grid of wide, tree-lined streets irrigated by special canals (aryks), and spacious avenues with characteristic marble cladding on Soviet public buildings. Against the backdrop of snow-capped mountains rising to 4.8 km, the city looks especially picturesque. Bishkek is a multicultural city: in addition to the titular Kyrgyz population (about 77%), a significant portion of residents are Russians, along with Uighurs, Dungans, Uzbeks, and other ethnic groups. This diversity is reflected in the city’s appearance and atmosphere, blending nomadic heritage, Soviet architecture, and modern Asian features.

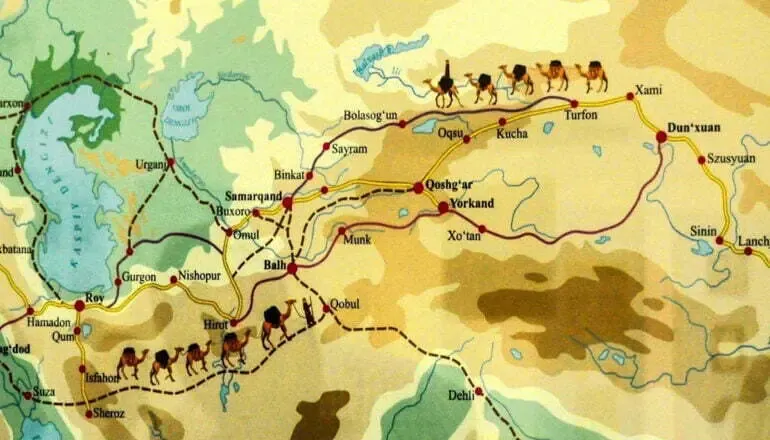

Long before the founding of the modern capital, this place bustled with caravan trade. As early as the 6th–7th centuries, a large settlement called Jul existed here - a transit point on the legendary Great Silk Road. The Jul settlement was a fortified trading town surrounded by earthen ramparts and moats, as confirmed by numerous ruins of citadels found nearby. Around Bishkek, about a hundred ancient settlements are known, with Klyuchevskoye and Kara-Dzhigach standing out in particular. These fortresses controlled roads through mountain passes and served the constant flow of caravans until the Mongol invasion of the 13th century, after which many fell into decline.

Archaeological finds testify to Jul’s importance as a center of trade between East and West. Excavations in the area of today’s Panfilov Park uncovered fragments of residential buildings and ceramics from the 7th–8th centuries, as well as coins from distant regions - Khwarezm and Bukhara. These artifacts confirm that merchants from various parts of Central Asia passed through Jul, making it an important transit hub for caravans. According to legend, travelers on the Silk Road stopped here to replenish their water supplies from local springs and exchange goods.

One notable fortification of that period is Klyuchevskoye, located on a high bank of the Ala-Archa River south of the center. Its name speaks for itself: proximity to springs supplied residents with water and offered caravans rest. The site consisted of a citadel and an artisan quarter. Archaeologists found traces of blacksmith workshops producing metal jewelry, tools, and horse gear - all essential for nomads and travelers on long journeys. Before the Mongol conquest, the area attracted various peoples - Turkic tribes, Sogdian merchants, and Saka nomads. After the destructive Mongol campaigns, Jul’s strategic importance waned, but the outlines of ramparts and layout of ruins still allow one to imagine the appearance of a medieval Central Asian city.

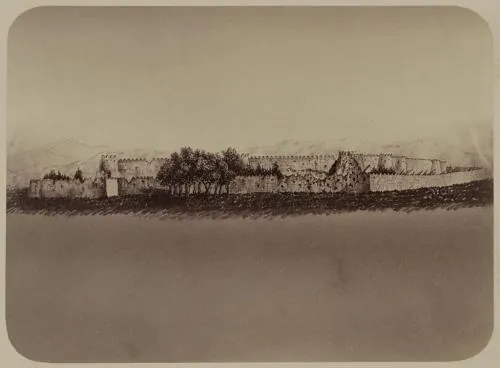

Several centuries later, the empty lands of Jul regained importance due to their strategic location. In 1825, seeking to strengthen control over the Chuy Valley, the Kokand Khanate’s troops laid the foundations of the Pishpek fortress. Built on the remains of ancient walls, it was a powerful fortification: a square citadel with four corner towers, surrounded by high crenellated mud-brick walls and a deep defensive moat. Located at the confluence of the Ala-Archa and Chu rivers, it controlled both banks and the valley’s main roads. Pishpek became a Kokand stronghold for collecting tribute from local Kyrgyz tribes and monitoring caravan routes from Ferghana and Kashgar.

Inside the fortress was a garrison of several hundred soldiers and warehouses with food and ammunition for prolonged sieges. It served not only a military function but also an administrative one - housing the Kokand governor and hosting trade with visiting merchants. However, confrontation between Kokand and the rising Russian Empire was inevitable. In autumn 1860, Colonel Apollon Zimmermann’s Russian detachment, with Kyrgyz support, stormed Pishpek and partially destroyed its fortifications. The final blow came in October 1862, when Cossack units again captured Pishpek and dismantled its walls almost to the ground to prevent reuse. The bricks and clay from the walls were used for building the surrounding settlement. Only fragments of the ramparts remain, still visible north of Jibek Jolu Avenue near the new central mosque - silent witnesses of Kokand rule.

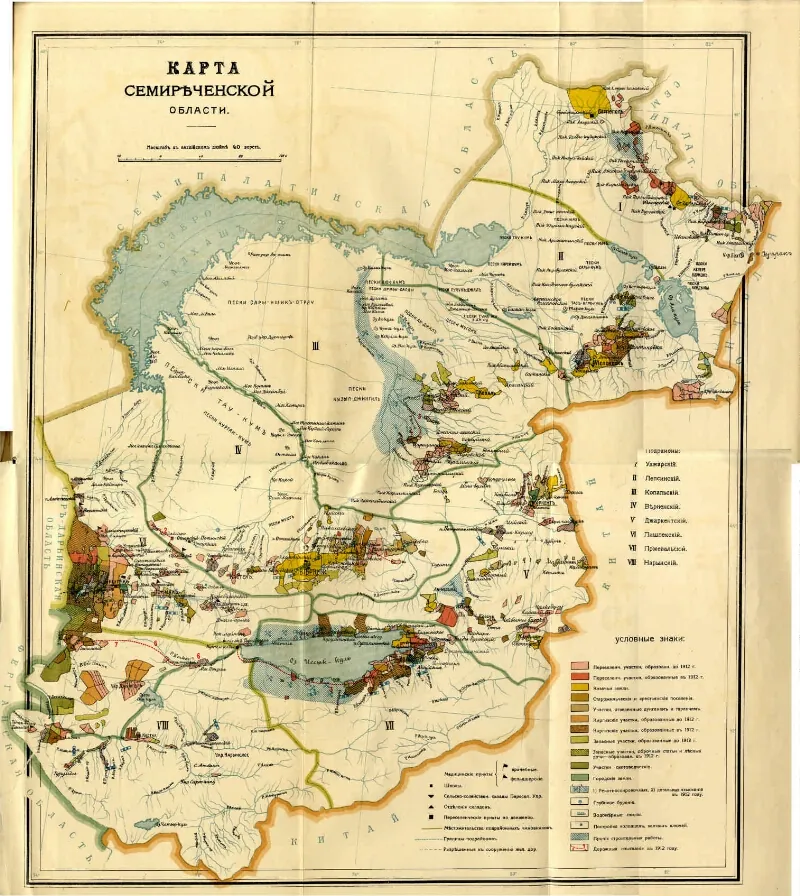

After the fall of the Kokand fortress, the region became part of the Russian Empire. In 1868, Russian settlers established the village of Pishpek on the site of the former fort, which quickly grew into an important postal and administrative hub of the Turkestan region. Its strategic position at the crossroads of postal and caravan routes fueled development. By 1878, Pishpek had been granted the status of a district town in Semirechye Oblast, becoming the administrative center of Tokmak District. From then on, the city was planned according to a rectangular street grid, simplifying the division into blocks and the construction of buildings.

By the late 19th century, Pishpek was rapidly expanding. From just a few hundred residents, the population exceeded 6,000 by 1897. Basic institutions emerged: a post station, telegraph office, the first brick factories, craft workshops, shops, and bank branches. In 1885, Pishpek was connected to other cities via telegraph, and in 1897, a nearby railway branch to Tokmak was built. Although the railway did not directly reach Pishpek, the station’s proximity improved regional connections. New settlers, mainly Russian and Ukrainian farmers, arrived, forever changing the city’s demographics.

By the early 20th century, Pishpek had become a multicultural district center. Alongside Kyrgyz and Russian settlers, Dungans and Uighurs from China, as well as Tatars, Germans, and others, lived here. On the banks of the Chu River, a multilingual bazaar bustled with trade - from wool, livestock, and leather to Chinese tea, porcelain, and Russian manufactured goods. Visitors could hear several languages at once, and traders were known for striking deals across cultural boundaries.

The city also acquired elements of a European provincial town: in the 1880s, an Orthodox chapel was built, and in the 1890s, the first public hospital with 15 beds opened for military personnel and locals. However, life was difficult - the area was marshy, malaria was rampant in summer (affecting nearly 40% of residents), and amenities were scarce. Only in the 1910s did authorities begin draining swamps and planting poplars and elms along streets, improving sanitary conditions.

In autumn 1917, Soviet power was established in Pishpek, marking a new chapter in its history. In 1924, the Kara-Kyrgyz Autonomous Region was formed within the RSFSR, and in 1925 Pishpek was declared its capital. In 1926, the city was renamed Frunze in honor of Mikhail Vasilyevich Frunze, a revolutionary commander born in the area. This began a Soviet transformation of the city. By the early 1930s, the population exceeded 50,000, fueled by rural migration and the arrival of specialists from across the USSR.

In 1936, when the Kyrgyz Autonomous Region became the Kyrgyz SSR, Frunze became its capital. The pre-war five-year plans spurred industrial growth: brick factories, food and light industry cooperatives, and agricultural processing plants appeared. The city center gained public buildings such as the Government House, House of Socialist Culture, and cinemas. During World War II, Frunze received dozens of evacuated factories and research institutes from European USSR. Thousands of workers, engineers, and cultural figures arrived, boosting development. Local factories produced ammunition, uniforms, and food; hospitals treated wounded soldiers. Over 50,000 residents were mobilized; many never returned, but their names live on in street names and memorials.

The postwar decades brought rapid urbanization and cultural growth. In 1951, Kyrgyz State University opened, marking the start of an academic and scientific cluster. By the 1960s, the central square featured a Lenin monument, the Kyrgyz State Opera and Ballet Theater, and the Russian Drama Theater. New wide avenues, residential microdistricts with panel housing, and parks were built. The straight, tree-lined streets and aryks (irrigation canals) for watering greenery made Frunze one of the greenest cities in Central Asia.

By the 1980s, Frunze was a major industrial and scientific center with machine-building, electrical, textile, and food industry giants, as well as research institutes. Cultural life thrived: local ensembles and theaters toured the USSR, and festivals were held. Public transport included trolleybuses and buses; new schools, libraries, and bookstores opened. Residents proudly called it the “heart of Kyrgyzstan.”

In the summer of 1991, as the USSR collapsed, Kyrgyzstan declared independence on August 31. Earlier that year, in February, the Supreme Council decided to restore the city’s historic name - Bishkek. The name is linked to a hero of epic tradition and also refers to a wooden churn used in making kumis, a symbol of nomadic culture. The new era brought both opportunities and challenges.

In the 1990s, Bishkek became the capital of the independent Kyrgyz Republic, hosting national government institutions. The 1993 constitution established a parliamentary democracy. The city faced the difficulties of transitioning to a market economy but retained its role as the main business and financial hub. In 1995, Bishkek instituted City Day on April 29, marking its 1878 founding as a district center of Semirechye.

The late 1990s and early 2000s saw major construction and urban renewal. In 1998, a new White House (Government House) was built, symbolizing sovereign Kyrgyzstan. Monuments changed: the Lenin statue was moved, and in 2003 the “Erkindik” (Freedom) monument was erected, later replaced by an equestrian statue of national hero Manas. By 2005, Bishkek had become a fast-growing metropolis attracting youth and entrepreneurs from across the country.

In the 2000s, a construction boom produced new residential districts, suburban cottages, and shopping and entertainment centers. Manas International Airport, 25 km northwest, was modernized to handle flights from dozens of cities worldwide. Bishkek remained multicultural, blending Kyrgyz traditions with Russian, Uzbek, Uighur, and European influences. The city hosted international forums, business meetings, festivals, and concerts. Today, Bishkek preserves the continuity of its epochs - from ancient Jul to Kokand Pishpek to Soviet Frunze - while looking confidently to the future.

Today, Bishkek is a modern Asian city where past and present coexist. Infrastructure is developing rapidly: wide avenues and new interchanges aim to manage increasing traffic, while high-rise business centers and residential complexes are being built. The historic center retains its 19th-century rectangular grid and lush greenery. Known as the “green capital,” Bishkek boasts numerous parks and squares, shaded by old plane tree and elm alleys. Its architecture is eclectic - monumental Soviet buildings like the Sports Palace, the UFO-shaped circus, and the marble Government House stand alongside glass business centers and stylish malls. At night, neon lights and illuminated fountains bring the city to life.

Economically, Bishkek is Kyrgyzstan’s main business hub, home to banks, corporate offices, markets, and exhibition halls. Dordoi Bazaar, one of the largest wholesale markets in the post-Soviet space, attracts thousands of traders and buyers from across Central Asia. Consumer goods from China, Turkey, and beyond are distributed from here to Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Russia. The city has supermarkets, malls, hotels, and business centers. Utilities have improved since the 1990s, with renovated water and heating systems, new junctions, and pedestrian zones. Still, Bishkek faces challenges like traffic congestion and aging housing, prompting plans for public transport upgrades, bypass roads, and Soviet-era district renovation.

The city’s public spaces are a source of pride. Ala-Too Square remains the heart of Bishkek, hosting national celebrations, parades, and concerts. Nearby parks and leafy boulevards, such as Panfilov Park and Erkindik Boulevard, offer leisure and cultural spaces for all ages.

Bishkek is the cultural heart of Kyrgyzstan, offering residents and visitors a rich variety of entertainment and educational opportunities. The city is home to dozens of museums, theaters, concert halls, and galleries. The main treasure trove of history is the National Historical Museum of Kyrgyzstan, located on Ala-Too Square. Reopened in 2021 after extensive renovation, the museum’s exhibits span the Kyrgyz people’s journey from ancient nomads to an independent state. Visitors can see Silk Road-era artifacts, a traditional yurt with household items, weapons and banners from World War II, and exhibitions dedicated to the country’s modern development. Interactive displays and English-language information make it popular with foreign tourists. Nearby stands the Toktogul Satylganov National Philharmonic Hall, an important concert venue hosting symphony orchestras, choirs, and dance ensembles.

The city’s theater scene is diverse. The Abdylas Maldybayev Kyrgyz National Opera and Ballet Theater, housed in a grand Soviet-era building with a colonnade, stages both classic operas such as “Aida” and “Eugene Onegin” and national ballets inspired by the “Manas” epic. The Chyngyz Aitmatov Russian Drama Theater stages Russian classics and contemporary plays, reflecting the capital’s multiculturalism. The Toktobolot Abdumomunov Kyrgyz Drama Theater offers performances in the Kyrgyz language based on national literature and folklore. Numerous private theater studios and youth troupes add vibrancy with intimate performances, poetry nights, and creative events.

Bishkek also boasts fine art galleries and specialized museums. The Gapar Aitiev Museum of Fine Arts houses a vast collection from pre-revolutionary Semirechye portraits to Soviet avant-garde works and contemporary Kyrgyz art. The Mikhail Frunze House Museum preserves the birthplace of the revolutionary leader, with authentic 19th-century household items, photos, and documents bringing old Pishpek to life.

Music thrives in Bishkek - from classical concerts at the Philharmonic to pop, jazz, and folk performances. The annual Jazz Bishkek Spring international festival draws musicians from around the world, becoming a symbol of the city’s openness to global trends. Other events include film days, contemporary music festivals, and art exhibitions at Oak Park Gallery and the Center for Contemporary Art. For more relaxed evenings, cinemas like the modern 3D “Kosmopark” offer the latest films.

The city’s gastronomy reflects its multicultural history. Traditional Kyrgyz cuisine, rooted in nomadic life, is centered on meat and dairy. Guests are often treated to beshbarmak - boiled meat (usually horse or lamb) served over hand-cut noodles with onions and broth. Its name, meaning “five fingers,” reflects the tradition of eating it by hand, symbolizing steppe hospitality. In colder months, hearty shorpo (meat broth with vegetables and spices) is popular.

Thanks to Uighur and Dungan communities, lagman (hand-pulled noodles with meat and vegetables in a spiced sauce) is hugely popular. Steamed manti dumplings and crispy samsa baked in tandoors are street food staples. Soviet-era favorites like borscht, shashlik, and Uzbek-style pilaf remain common. Bishkek is also one of the few capitals where you can find Dungan cold noodles ashlyam-fu and Korean-style pickled salads - a legacy of the Korean diaspora.

Sweet lovers will enjoy local treats like chak-chak (honey-coated fried dough), baklava, dried fruits, and nuts. City bazaars overflow with fresh produce, spices, mountain cheeses, and fresh tandoor bread. Fermented mare’s milk, kumis, is a unique local specialty with a refreshing, slightly alcoholic taste.

Bishkek’s dining scene ranges from traditional tea houses decorated like yurts to modern coffee shops, steakhouses, pizzerias, and sushi bars. Family-friendly cafes serving both European and Asian dishes are popular, as is street food culture - from samsa and shawarma to grilled corn and chicken wings. Bishkek’s culinary landscape blends nomadic heritage with international flavors.

Bishkek is Kyrgyzstan’s key transport hub. Manas International Airport, 30 km northwest of the city, connects Bishkek with major Eurasian cities such as Moscow, Istanbul, Dubai, Delhi, and Almaty, as well as domestic destinations like Osh and Jalal-Abad. Airport access to the city takes about 30 minutes by express bus or taxi.

Rail service is limited: a branch of the Turkestan–Siberia Railway runs from Bishkek to Balykchy (on Issyk-Kul Lake) and to Russia via Kazakhstan. Road transport is more significant, with highways linking Bishkek to neighboring countries. The 240 km trip to Almaty takes 4–5 hours, and the southern route to Osh crosses the scenic Too-Ashuu Pass. Eastern roads lead to Issyk-Kul and onward to China via the Torugart Pass through Naryn.

Public transport includes buses and marshrutkas (minibuses) covering main routes. Affordable taxi services like Namba Taxi and Yandex Go are widely used. Bicycle lanes and e-scooter rentals are expanding, though Bishkek has no metro. The city’s compact layout makes walking between attractions easy.

Internet and mobile coverage are extensive, with 4G networks and free Wi-Fi in many cafes and malls. ATMs and currency exchange points are plentiful, and most businesses accept bank cards, though cash is useful for markets and minibuses. Bishkek’s accessibility and modern amenities make it both a comfortable long-term base and an ideal starting point for travel in Kyrgyzstan.

Today, Bishkek is a city of contrasts and opportunities, where you can sip tea while hearing tales of nomads, then use a ride-hailing app to reach a modern business center. Its ancient roots in Jul, Kokand-era Pishpek, and Soviet Frunze have grown into a vibrant capital that honors its past while embracing the future. Green parks, the aroma of pilaf and fresh bread, the sound of the azan over the old city, and the smiles of locals all make Bishkek the welcoming heart of Kyrgyzstan.

Forgotten Rivers and Mountain Peaks: A Journey Along the Southern Shore of Issyk-Kul is a three-day tour that immerses you in the unique natural beauty of Kyrgyzstan.

In two days, we'll ascend to 3500-meter peaks, sit by the campfire in the heart of the Tien Shan range by Lake Son-Kul, and have an amazing time

This route combines the picturesque mountain canyons of Kok-Moinok, Lake Issyk-Kul, the taste of national cuisine and a trip along one of the most beautiful roads in the country – the Boom Gorge.

Experience all the beauty of Kyrgyzstan's nature behind the wheel of a comfortable and daring BMW F650GS tour enduro. These impressions are worth any money and will never be forgotten.

Visit two pearls of Kyrgyzstan in 1 day on a car tour

Visit the Valley of the Seven Bulls, see Issyk-Kul and relax in the thermal springs